For the past decade, Bethany has focused on better understanding digital transformations to production, performance and persona of public figures and its relationships to journalism. Her discussions of networked and constructed reality so far have analysed the online performances of political leaders, journalists, celebrities, social media influencers across lifestyle and crime and criminals themselves, including terrorist organisations.

“In the first decade of the 21st century, networked – multi-platform and concurrent – media environments transformed journalism, celebrity and political cultures.” (Usher, 2020: 142)

Bethany’s first major topic of research focused on the shifting relationships of networked reality between social media site Twitter, news website MailOnline and celebrity culture, including the emerging genre of “constructed reality” television shows.

In “Twitter and the Celebrity Interview” (2015), she highlighted how older news discourses were shaping the self-presentation of celebrities on social media and their interactions with fans, in order to become a new practice of persona and promotion.

Her exploration of how MailOnline became the biggest English-language news site in the world between 2008 and 2013 for the Press Gazette demonstrated how the “sidebar of shame” worked as part of networked reality practices. Content increasingly relied on self-performances of celebrities on social media sites.

Chapter six of Journalism and Celebrity (2020: 142-168) expands this to this to explore how networked applications further hyperconsumerism and neopopulist politics.

“”The Kardashians became the first networked reality stars because their self-brand constructs a cross-media ambience of hyperconsumerism and indoctrinates their become active participants in promotion.” (Usher, 2020: 152)

Lifestyle Influencers

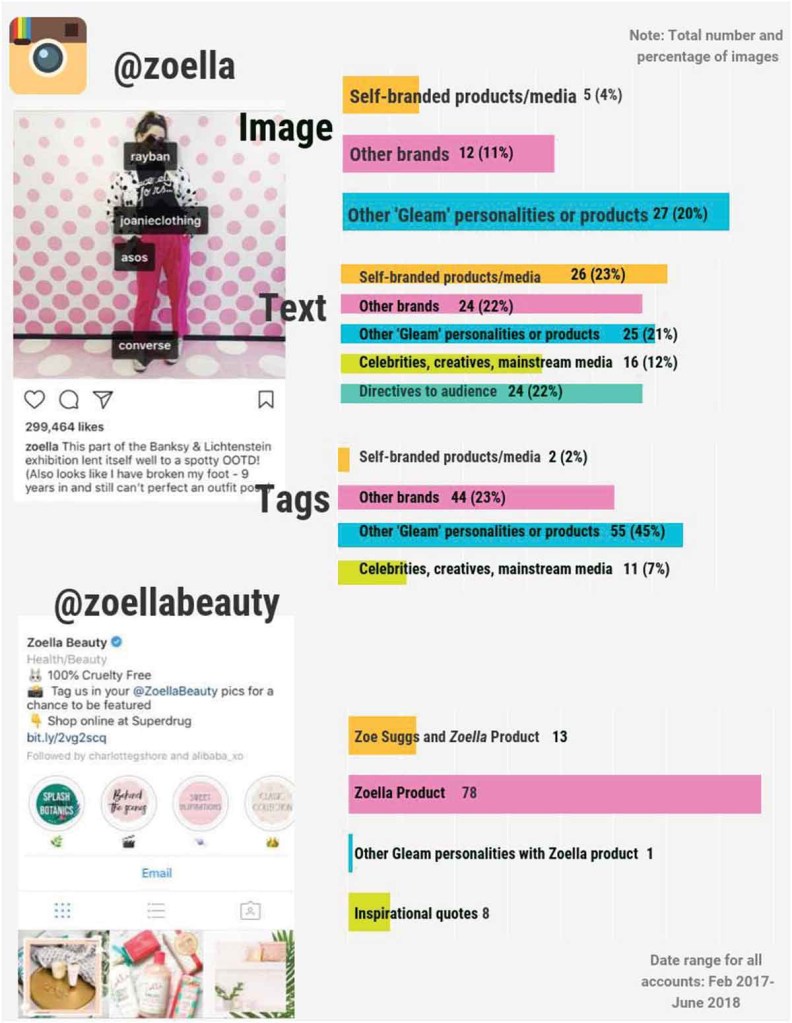

“Rethinking Microcelebrity: Key points in practice, performance and purpose” (2018) expanded analysis of how networked reality perpetuates consumer culture.

It considered shifts resulting from the popularity of Instagram and considered how influencers had professionalised through examining the networked reality practices of pioneering “digital first” talent agency Gleam Futures, and how they had transformed the production practices of influencing culture.

This work explored the “repressive ambience of hyperconsumerism” for both influencers and their fans and new constructs of visual reality, which layer consumer elements into everyday images.

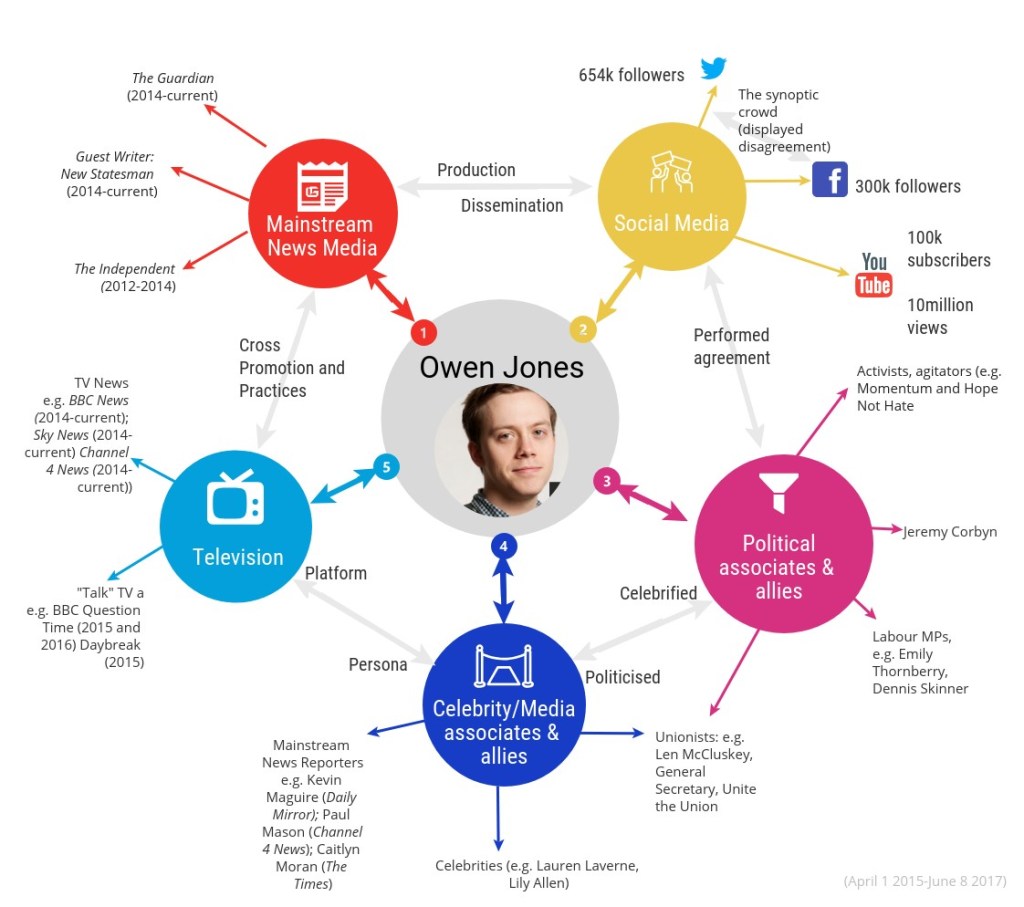

Bethany expanded these ideas to consider how it was shaping performance of both politicians and political commentators. Analysis highlighted the similarities with influencer and celebrity culture and how audiences seemed to now relish “spectacles of opinion”.

“By 2020, we better understood network realities’ capacity to shape public spheres as part of agglomerations of socio-economic and political power” (Usher, 2020: 144).

“The Celebrified Columnist and the opinion spectacle: journalism’s changing place in networked public spheres” (2020) compared two British journalists – one far right and one left – to illustrate fundamental similarities in production practices, including the use of networked reality structures.

The professional practices of journalists also encompass self-branding practices of celebrities and persona construction in networked media environments increases visibility and reach, with followers, clicks, shares and likes, the markers of professional success.

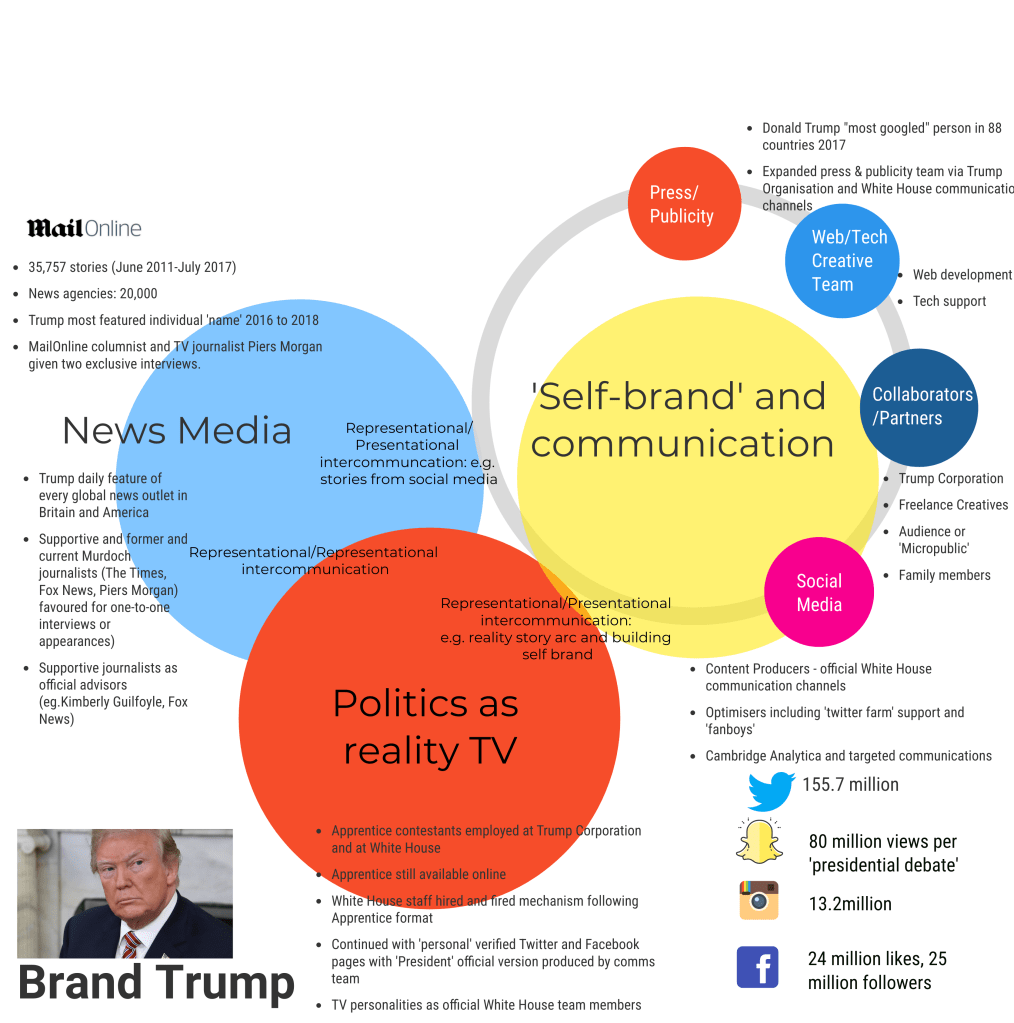

developing and maintaining “Brand Trump”

Political Leaders

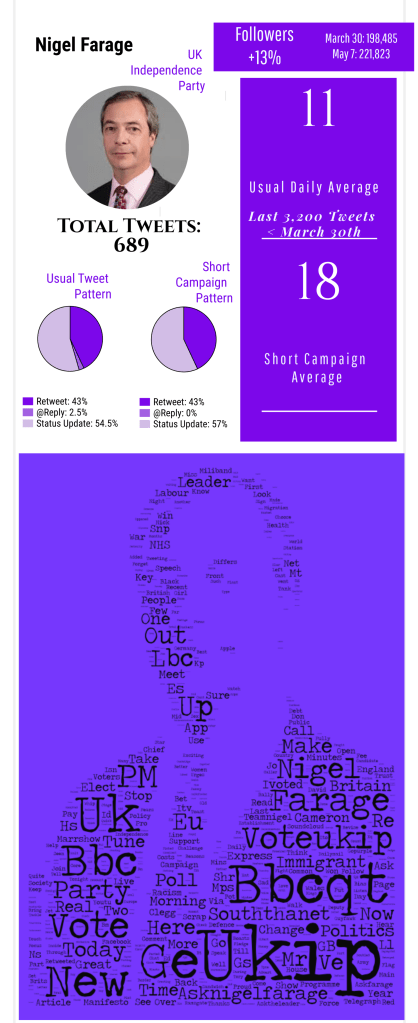

During the 2015 General election, research focused on analysing the networked reality practices of political leaders in the UK.

In what was declared “the first social media election”, the relationships between social media, persona construction and the press became more complex and shifted across different mediated dimensions of time.

“You, Me and Us”: constructing political persona on social networks” highlighted how older campaigning narratives were shaping networked reality. Analysis of all social media posts across Twitter, Facebook and YouTube also identified key parameters of change for campaigning performance and communication with voters.

Her analysis of the practices of then UKIP leader Nigel Farage highlighted a number of key changes that influenced the campaigning practices of Donald Trump in the presidential election the following year.

The complex communication ecosystems that emerged, maintained journalism and celebrity’s places in constructing reality and created new networks for extreme right wing ideology. Bournemouth University Press published a short summary discussion of the relationship between Farage’s performance and Trump’s as part of their election analysis.

Bethany’s most recent explorations of networked reality in Journalism and Crime argues how it is shaping new and current work in terms of crime cultures and simulative dimensions. This expands beyond media and shapes the networked reality practices of criminals themselves.

“Networked – multiplatform and concurrent media environments have also transformed the relationships between journalism and crime, patterns of “notorification” and political and legal cultures-of-authority”. (2023: 234)

Chapter seven of Journalism and Crime (2023) – “Neoliberal tabloidism and hypercriminality” Bethany argues that the networked digital ecosystems of are a thundering crescendo of the image-led news and dynamics of tabloid culture.

The algorithms that form it are best visualised as a pulsating, growing, shape-shifting dark mass, which amplifies and expands dimensions of certain types of crime, victims and notoriety.

This also means there are ever more simulative dimensions to both journalistic and other forms of media practice within the network.

News aggregation and the synoptic and panoptic interplays between journalists, true crime influencers and criminals are becoming drivers of action.

There are some jarring examples of the human costs of hypercriminality, such as the brand-building success of Islamic State. Analysis reveals how by employing the networked reality self-performances of influencers they successfully shifted the news agendas of mainstream British newspapers.

Her analysis also considers how journalists use crime as clickbait, as considered for The Press Gazette and argues for necessary changes to codes of practice.

“Networked and constructed reality production practices were crucial to the development of Brand Islamic State, which existed as a signifier and a reality network long before the Islamic State existed in reality and was the principle enabler of its existence.” (Usher, 2023: 243 ).

What next?

The algorithms that now form networked reality are best visualised as a pulsating, growing, shape-shifting dark mass, which amplifies and expands visibility of certain individuals and certain types of news media. The content that is programmed into algorithms and A.I train behavioural patterns and how it can be trained to pay attention to some content and ignore others. It makes biases more likely to happen. Bethany began to explore these ideas in Journalism and Crime and will be expanding this work